Rohingya dads protect children from violence

Refugee fathers unite to protect children in camps

Here in the UK, we’ve seen how the tension of lockdown and the fear of COVID-19 have manifested themselves in increased cases of violence in the home. Sadly, the same is true throughout the world.

The threat of coronavirus has been looming over refugee camps for many weeks now. Near Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh, refugees from Myanmar’s conflict have been on lockdown since mid-March.

And now, on 2 June, confirmation that a 71-year-old man has died from Coronavirus, will only heighten emotions.

A perfect storm

A new World Vision report, Aftershocks – A Perfect Storm, looks at information from our programmes, alongside call volumes to children’s helplines and domestic violence reports from around the world.

Its findings give a stark warning that parents and caregivers are increasingly turning to physical aggression as the financial and emotional pressures of the pandemic worsen.

The report reveals that in Bangladesh:

- Cases of children being beaten by parents or guardians shot up by 42% in April 2020

- There was a 40% increase of calls to the child helpline

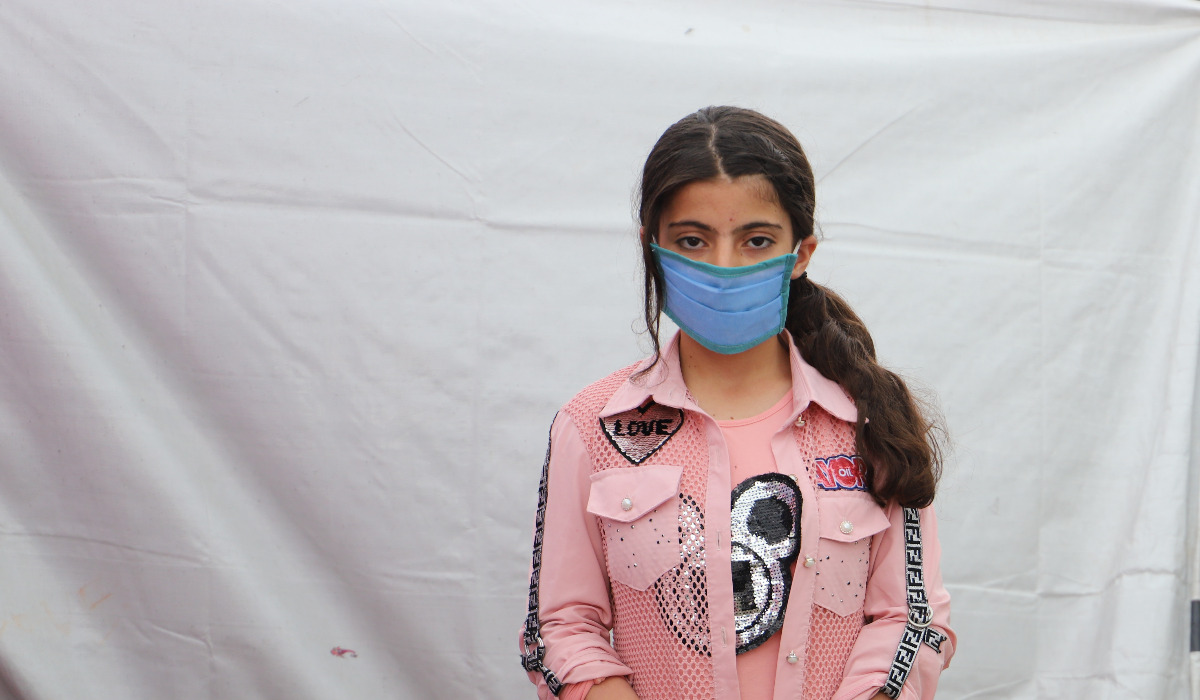

- 50% of those interviewed said the safety and security of girls was an issue in the lockdown

Andrew Morley

President of World Vision International

Trapped in a camp

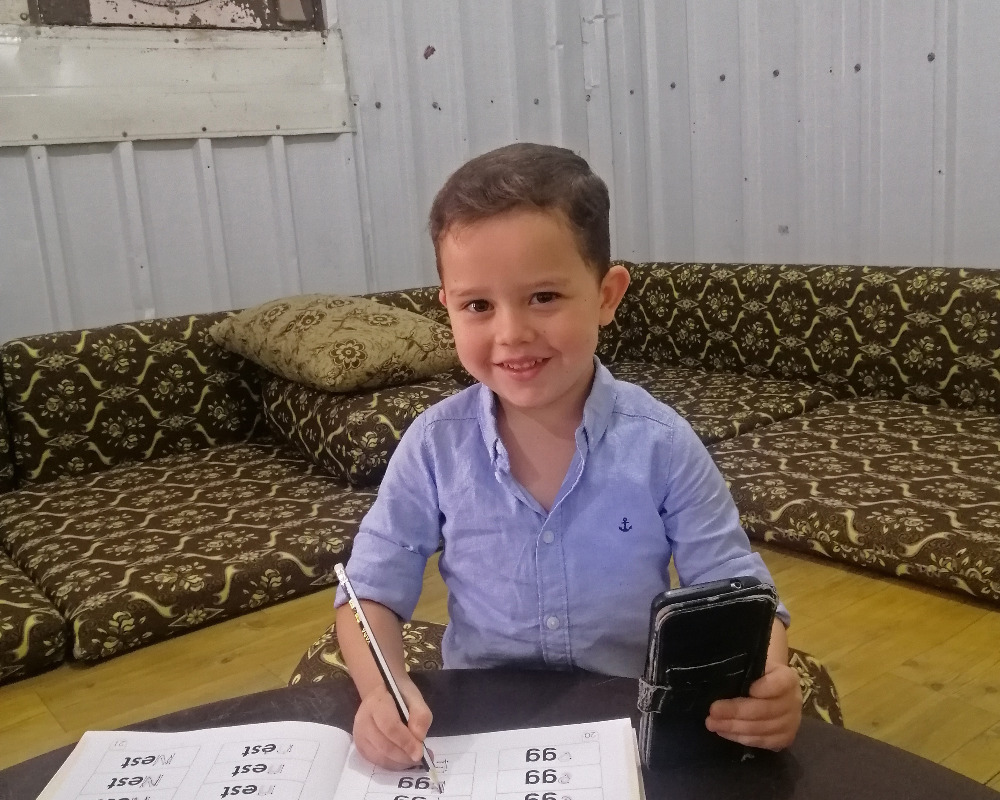

Living in cramped, unsafe conditions children in the camps are deeply exposed to the cruel effects of this pandemic – including violence – with no means of escape and no-one to turn to for support.

As part of our global response to the pandemic, World Vision is working to reach as many vulnerable refugee children as possible.

Local defender

In the meantime, local leaders are taking on the challenge. Obaidur, a respected Rohingya majhi (camp leader), believes that with good teaching, men can create positive change in the heart of the crisis.

“There are many reasons why quarrels and physical violence happen in the camp,” says Obaidur.

“Men cannot provide food for their families, and there are shortages. Women ask, ‘Where is the salt and oil?’ Men cannot buy them because they can’t earn an income. Men get angry; women don’t listen. Quarrels happen in the family and escalate in society."

Obaidur is part of a men’s group aimed at addressing gender-based violence in the camps, and says many issues come up when they meet in the new community centre.

“We have learned many good things sitting together,” he says. “When our NGO brothers share new things and techniques with us, we can adopt and apply them in our families.”

Despite the many challenges, Obaidur and his fellow group members want to build peace in the camp where they have been living for almost three years. They have been identifying the root causes of violence against women and children and finding temporary solutions.

Preventing and stopping violence is not easy in the camps where stress levels run high as couples struggle to feed their children while worrying about their future. But the father of eight boys is already using what he’s learnt in his own family.

He says, "For example, I now know that women should be respected for their work. Sometimes they get stressed because they have many household chores. So, I help my wife to cut vegetables, collect water and other small tasks."

Leading the community

Before fleeing conflict in Myanmar, Obaidur held great responsibility and influence in the Rohingya community: “I was a chairman of 11 villages with nearly 14,000 families. Most were farmers,” recalls Obaidur. “People were very hard-working. I used to farm 20 acres of land. I had 70 cows and 50 goats. I owned one bus and two trucks.”

Today, he lives in a 10x16 square foot, one-room shelter with his family, alongside almost 860,000 fellow refugees. For food and other basic needs, they depend on aid from humanitarian organisations, like World Vision.

But he’s still a figure of authority, realising that in these most difficult times, he – and those around him – can work together to make it a little better.

With the men’s group, Obaidur has identified that, as well as domestic violence, there are grave abuses affecting children in the community, including child marriage. Child marriage is a cultural tradition among the Rohingya and is seen as a way of protecting girls from the risk of rape or abuse.

Unfortunately, the findings of Aftershocks – A Perfect Storm echo this, predicting an increase in child brides and child labour as financial difficulties take a toll on struggling families. We estimate that, potentially, at least four million more girls could be married in the next two years.

Obaidur remains positive though, believing these man-made issues can be solved by men. “If we want, together we can stop child marriage. [It is] a curse to our society.”

Andrew Morley

President of World Vision International

Calling all hidden heroes

More than 12 million refugee children around the world need governments to step up and protect them from the impact of this pandemic, both now and in the future.

This includes urgently increasing funding for health, education and other social services that protect children from all forms of violence and abuse.

In the meantime, Obaidur says he and his fellow group members believe that their efforts are contributing to a reported drop in family violence, child marriages, dowry giving and community quarrels in their block.

We need more Obaidurs in our communities, protecting children and supporting families – especially now.