Child labour: “60 pockets an hour”

Bithi has been forced to work since she was just 12 years old

15-year-old Bithi has been working at a garment factory for the past three years. She is one of four million Bangladeshi children that are employed. Bithi longs to be at school with girls her own age, but she already feels it is too late.

The needle hums, fingers fly and piles of cloth are stitched together at record speed.

“60 pockets an hour,” the 15-year-old behind the sewing machine quietly tells us. Squished inside a second story room with 20 other Bangladeshi women, the girl hunches over her machine while fluorescent lights beam hard overhead.

Bithi is one of the thousands of Bangladeshi children piecing together designer jeans that she’ll never be able to afford. Crippling poverty and a sick father has forced Bithi’s family to send their two eldest daughters to the garment factories to sew clothes that will be sold in shops in Canada, the United States and other high-income countries.

But that was three years ago, when Bithi was 12. Now, it’s routine – no more tears are spilled. Every day, Bithi helps create a minimum of 480 pairs of trousers for 83.3 taka - just 73p.

In a way, Bithi feels grateful for the work. She tells us confidently that her factory is a ‘good one.’

Her boss, 24-year-old Muhammad, speaks of Bithi highly. He tells us that she is a good worker and he quickly promoted her from factory helper to machine operator.

Muhammad’s shop is small – sub-contracting jobs from other larger garment factories – and government policies regarding child labour go unheeded, like in so many other places.

“The wages we’re giving at this factory are not enough, even me, in charge, I feel that,” he admits glumly.

Still, for Bithi, it’s okay. She says the job has no problems, no perilous fires and a nice boss. Bithi tells us that on one occasion, the sewing machine needle stabbed her finger and when it kept on bleeding she was able to take the rest of the day off to heal. She tells us that in many factories, this would never have been allowed.

Bithi’s mother, Feroza, is unapologetic about sending her two eldest daughters to the garment factories before they were even teenagers. We met her in the family home, where all eight members share one bedroom.

A few years ago, Feroza’s husband was very sick. He couldn’t work, and the family was facing a crisis.

“There was no food, not even rice. I cry when I remember those days. I thought it’s better for us to die than to not have food,” Feroza tells us.

For a year and a half, Feroza juggled domestic work, raised six children, and ran a bag making business. Still, she couldn’t make ends meet. Food was begged and borrowed from charitable family members and neighbours. At night the children cried from hunger pains.

Charity was running out; Feroza knew that something had to change. So she did what her parents did to her when they arrived in Dhaka decades ago. Feroza sent her eldest daughter, Doli, to work in a garment factory at age 12.

And when Bithi was 12, she too was sent to work in a factory.

"As a mother, I feel sad but I still have to be realistic," Feroza says bluntly.

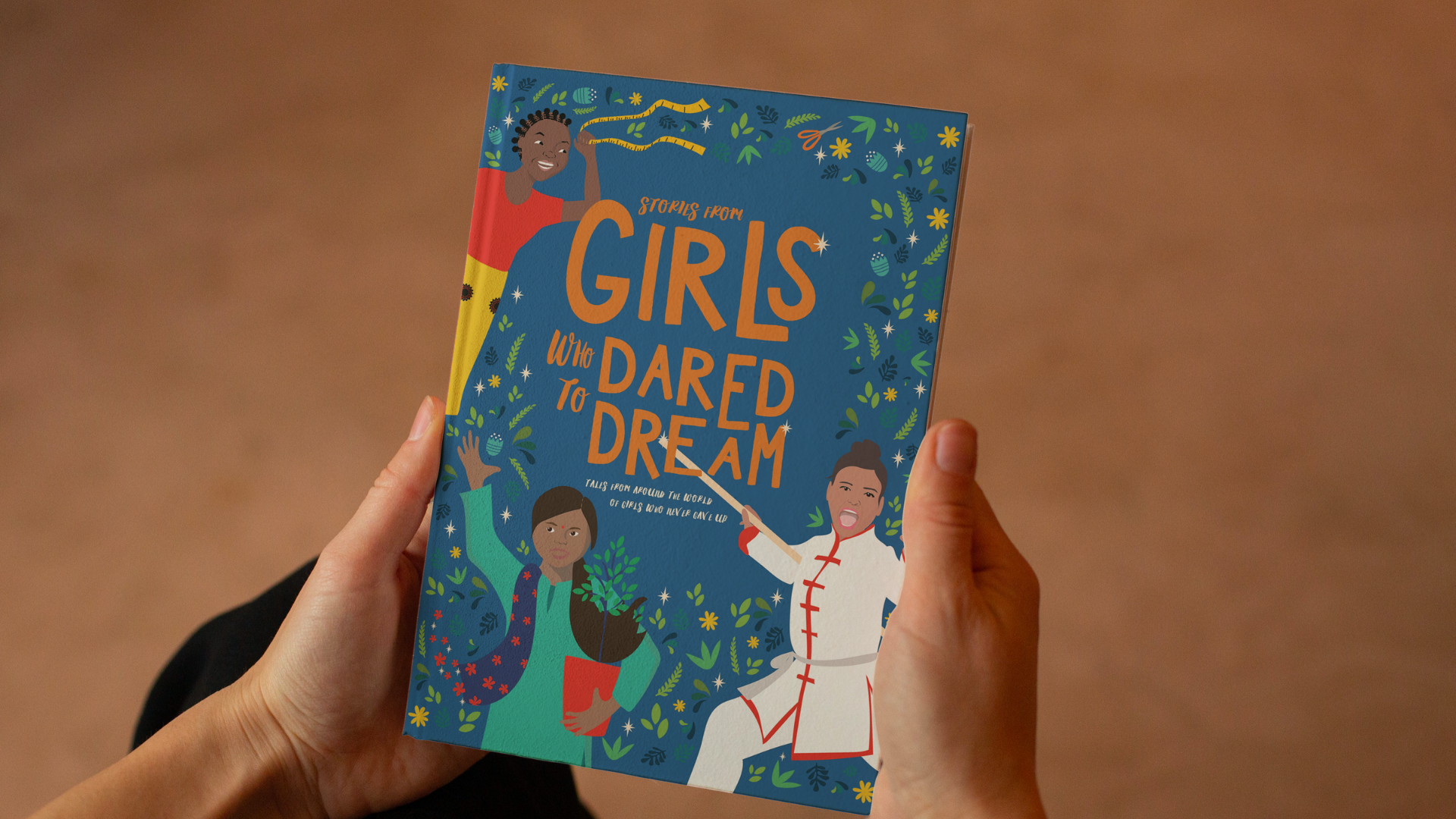

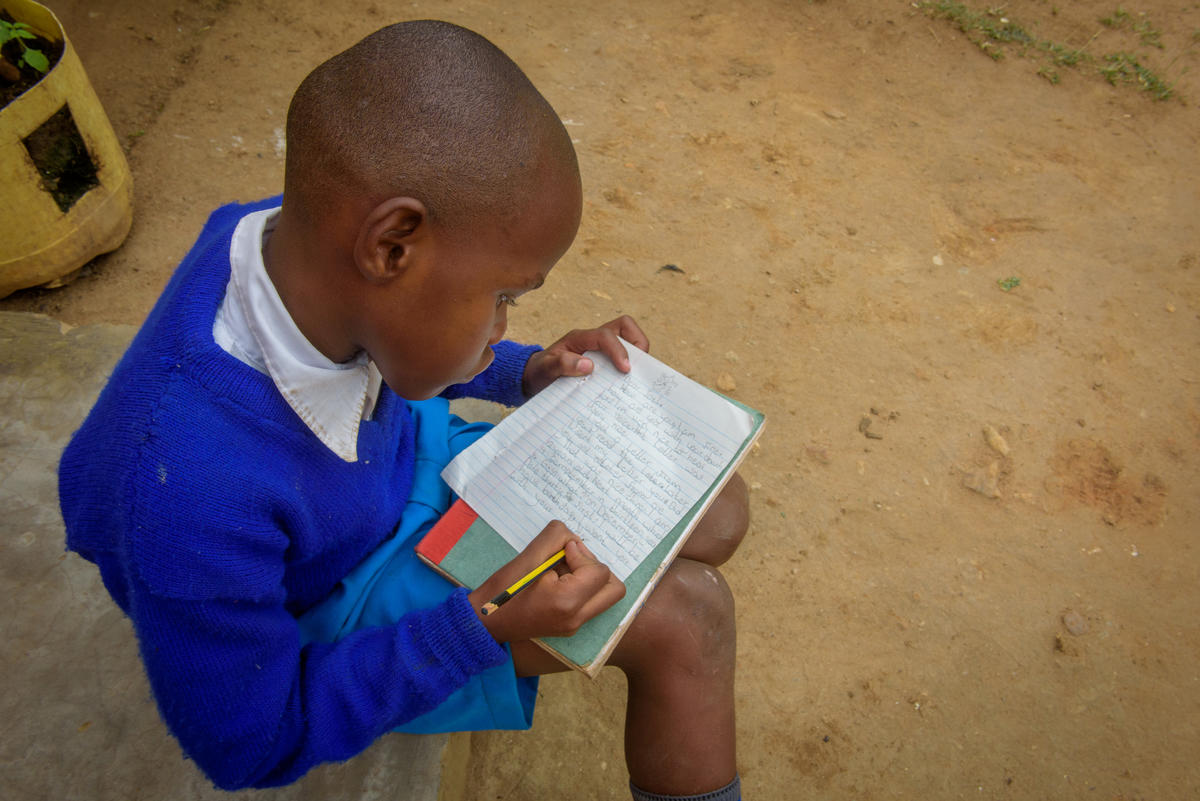

Bithi tells us that when she sees other girls her age in their blue and white-checkered school uniforms, it ‘breaks her heart.’ She once had a dream for the future, to be a doctor, but she’s given up on that dream.

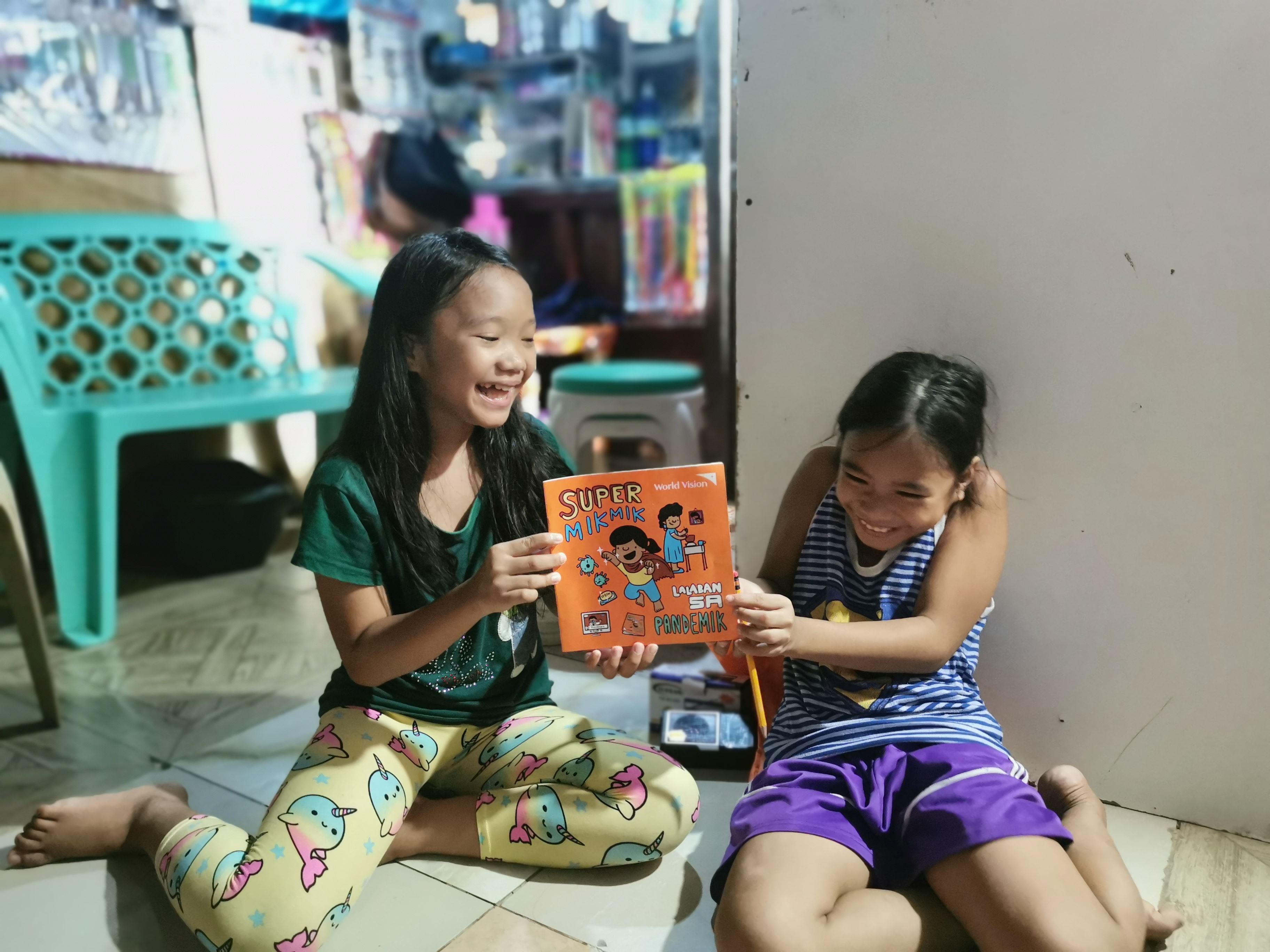

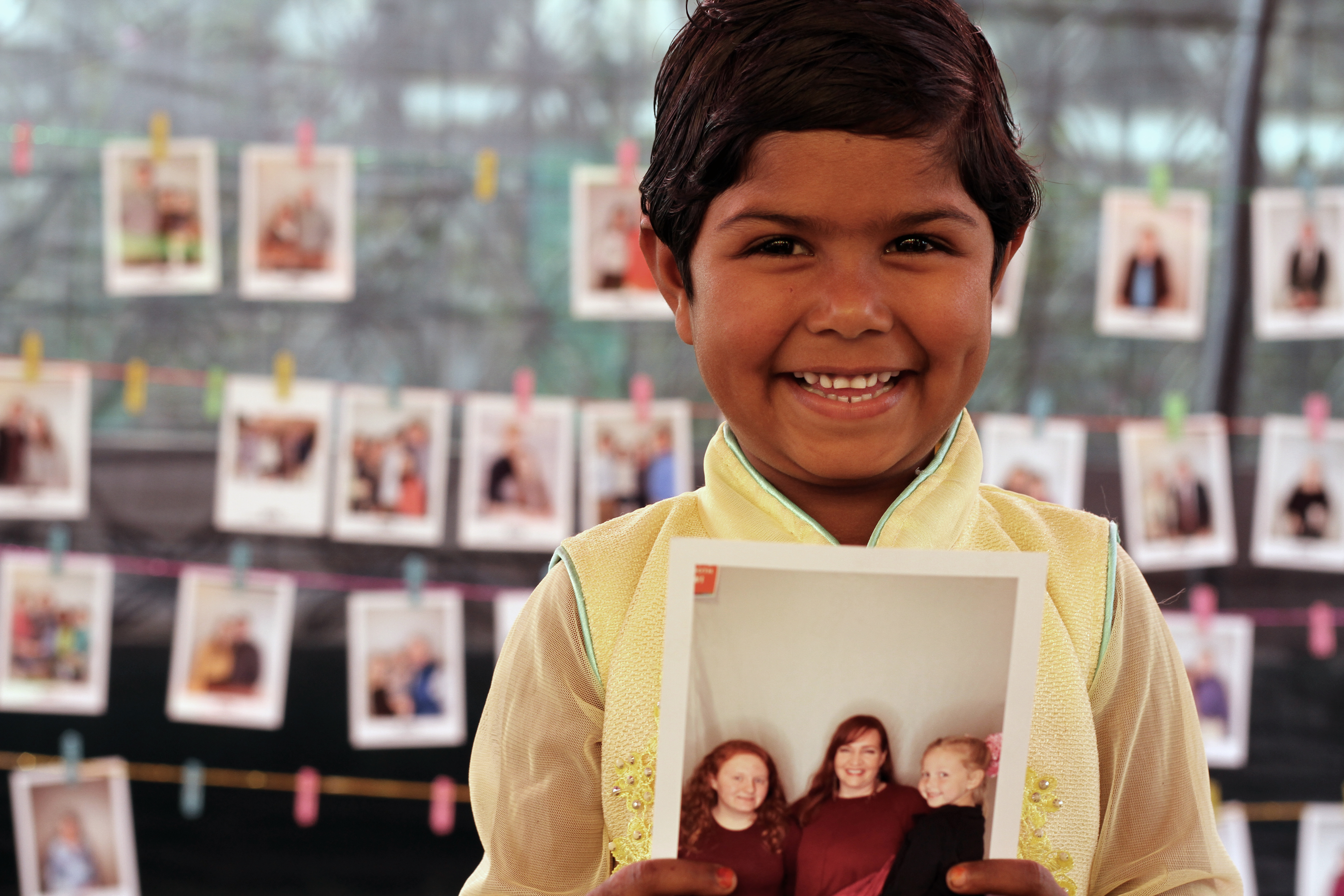

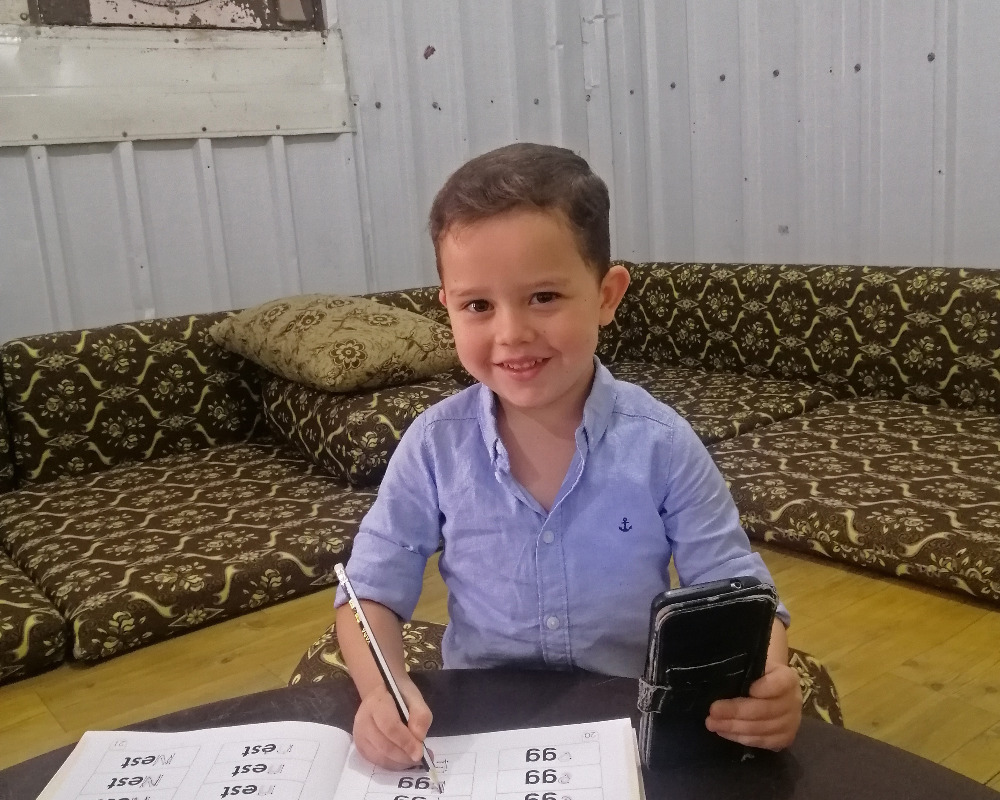

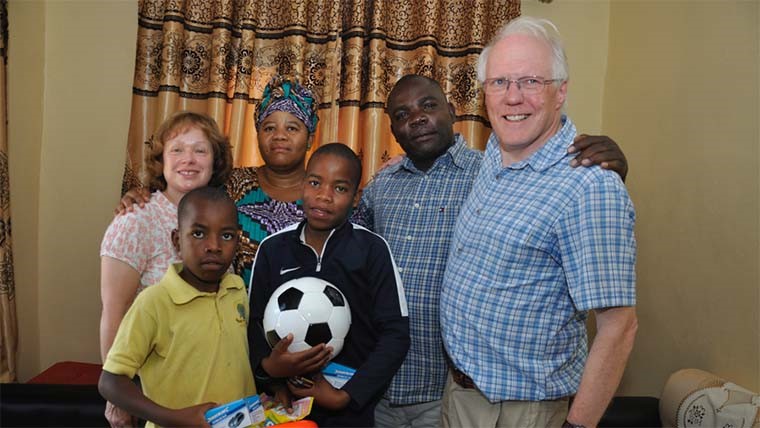

World Vision works around the world through child sponsorship and other projects to help reduce children’s vulnerability to trafficking, abuse and exploitation. In Bangladesh, a total of 161,231 children from vulnerable communities have been reached by our Child Safety Net Project that aims to help children like Bithi. You can find out more about child sponsorship below.